Unlocking the brain’s secrets: How epilepsy genes affect different regions

For families of children with severe epilepsy, controlling seizures is often just the beginning. Even when medications can reduce seizures, many children still struggle with learning difficulties, behavioral challenges and sleep problems that disrupt daily life.

New research from the UCLA Broad Stem Cell Research Center helps explain why treatments often fall short, revealing that a single disease-causing gene variant can affect different parts of the brain in strikingly different ways.

The study focuses on a rare childhood condition called developmental and epileptic encephalopathy type 13, or DEE-13, caused by variants in the SCN8A gene. This gene produces a protein crucial for electrical signaling in the brain. Children with DEE-13 experience frequent seizures along with developmental delays, intellectual disability and features of autism spectrum disorder.

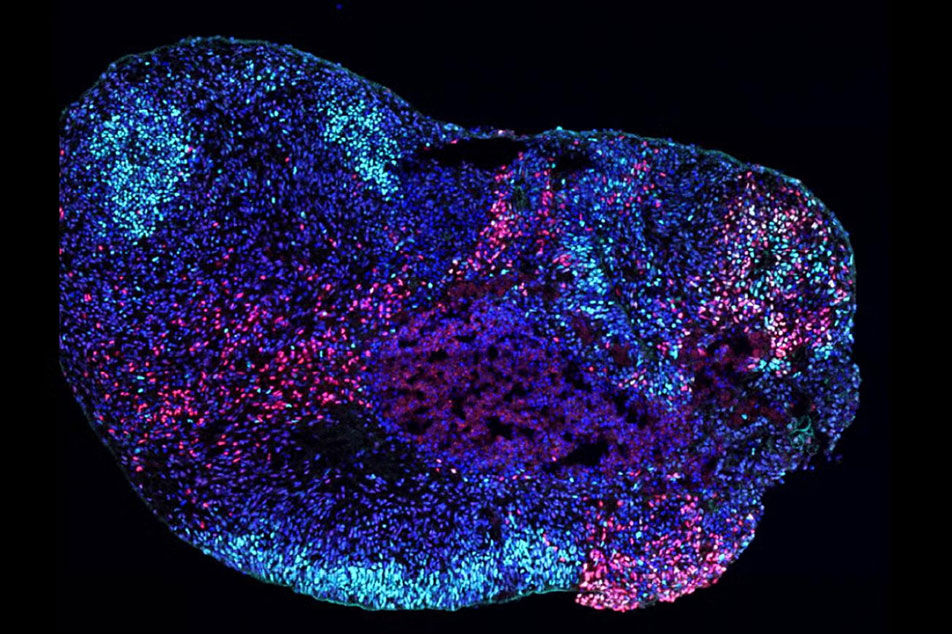

Using patient-derived stem cells, UCLA researchers Ranmal Samarasinghe and Bennett Novitch created advanced 3D models of two key brain regions: the cortex, which controls movement and higher-order thinking, and the hippocampus, which supports learning and memory.

The results were striking. In the cortex, the gene variants made neurons hyperactive, mimicking seizure activity. But in the hippocampus, they disrupted brain rhythms critical for learning and memory by selectively destroying specific inhibitory neurons — the brain's traffic cops that keep neural activity in check.

“Seizures are what bring families to the clinic, but for many parents, the bigger daily struggles are the other symptoms — problems with learning, behavior and sleep,” said Samarasinghe, a clinical neurologist and assistant professor of neurology. “What we found is that these cognitive problems aren’t just side effects of seizures. They likely arise from distinct disruptions in the hippocampus itself.”

To confirm their findings, the team compared brain recordings from people with epilepsy to their stem cell models. Abnormal brain rhythms were observed in both patients’ seizure-prone regions and in the lab-grown tissues carrying SCN8A variants, while healthy regions showed normal activity.

Beyond its implications for epilepsy treatment, the research represents a major technical advance. This is the first study to successfully create and characterize brain rhythms in human hippocampal models.

These models could become powerful tools for testing whether experimental therapies can restore healthy brain activity, potentially leading to treatments that address not just seizures, but the cognitive and behavioral challenges that affect daily life.

“This is a foothold into a whole new area of research,” said Novitch, a professor of neurobiology. “We now have a system to ask how different diseases affect learning and memory circuits, and in the future to explore whether experimental therapies might improve brain activity in these models.”